Recoral

Growing corals on offshore wind turbines

With our ReCoral project, we aim to support natural coral growth in our Greater Changhua offshore wind farms in Taiwan. If successful, we hope to scale up this coral restoration method to use on other offshore wind farms with similar ecology. ReCoral is a proof-of-concept trial in partnership with the Penghu Fishery Research Center – a research institution specialised in aquaculture and marine biology, under the Taiwan Ministry of Agriculture.

Our non-invasive method involves collecting coral spawn that washes up on the shoreline of the Penghu Islands, cultivating it in the laboratory, transferring viable corals to customised metal frames, and then introducing them to designated locations on turbine foundations, with the intention that they will settle and grow there.

Corals live in symbiosis with an algae called zooxanthellae that relies on sunlight for photosynthesis, meaning they must live near the surface.

But these algae can be badly harmed if the water becomes too warm, too polluted, or too often exposed by extreme low tides, resulting in coral bleaching. As the impacts of climate change accelerate, coral bleaching occurs more and more frequently in the shallow waters where corals live naturally.

Within an offshore wind farm, the corals will be protected from extreme temperatures by the natural circulation of the cooler, deeper water the turbines stand in. Living further out to sea, the corals are also protected from frequent human disturbance.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, more than 500 million people around the world depend on coral reefs for food, storm protection, jobs, and recreation1.

As a leading renewable energy company, we’ve made the fight against climate change our core business through the deployment of green energy solutions.

But we want these solutions to do more than generate green energy. We’ve set the ambition to achieve a net-positive impact on biodiversity for every new project we commission from 2030 onwards.

Coral cultivation

The ReCoral project applies non-invasive sexual reproduction method to coral cultivation. The method allows genes to intertwine and evolve coral species, increase genetic diversity, eventually allowing them to adapt to changes in their habitat.

Our method begins on the shorelines of the Penghu Islands off the west coast of Taiwan. With consent from local government and guidance from the Penghu Fishery Research Center, marine biologists collect coral spawn along the shorelines that have been released in the annual mass spawning event trigged by a full moon in spring. They take them to the Penghu Fishery Research Centre for seeding and cultivation.

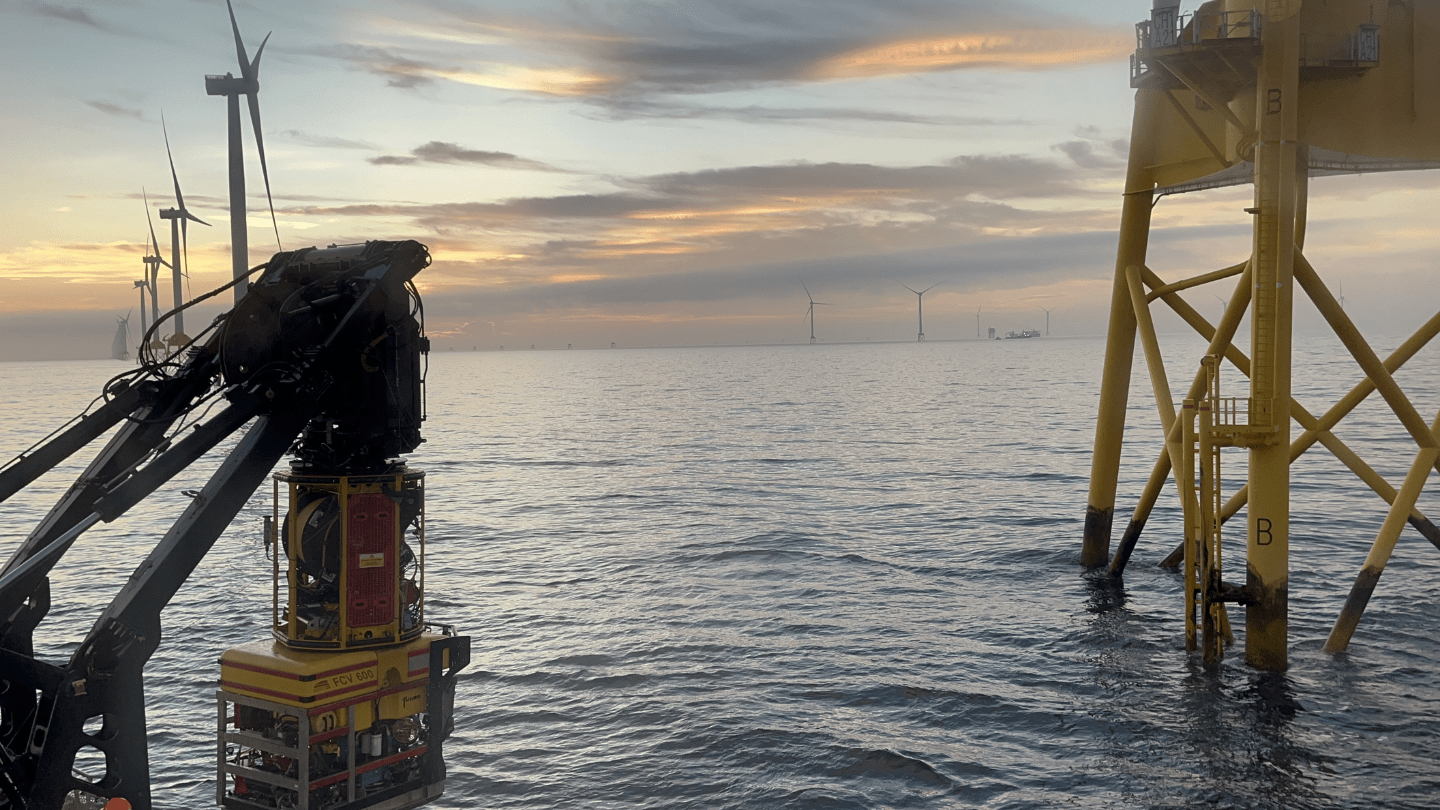

Offshore coral deployment

The project team has repeated the method for three consecutive years from 2022 to 2024. The corals are then nurtured in the lab for at least six months to ensure they are healthy and strong enough to adapt to the offshore environment.

At the offshore wind farm, the corals are secured using a custom-made aluminium frame with pre-bolted energise-to-release electromagnet sets. The designated location is around five to ten metres below the lowest tide level, allowing the corals to receive adequate light and providing access for deploying the cages and monitoring the corals using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs).

In June 2022, we completed our first seeding trial, using coral spawn collected from the spring mass spawning event, and a mesh cage that we attached to one turbine foundation piece. Early monitoring shows that the corals did not achieve the growth rates we expected.

This first attempt allows us to refine our approach for the next trial. We gathered the following learnings:

Ultimately, we hope to refine a method that can be deployed at a much greater scale than the trial at Greater Changhua offshore wind farms. If we are successful, this coral restoration method could be applied to the foundations of offshore wind turbines in any tropical waters around the world, boosting ocean biodiversity.